INTRODUCTION

Abnormal embryonic development of the systemic and pulmonary venous system results in a wide spectrum of congenital venous anomalies1-4. These anomalies may occur as isolated findings or in association with complex congenital heart diseases (CHD)1. While some remain asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally, others may present with significant cardiorespiratory symptoms requiring urgent surgical intervention1,4,5. Accurate delineation of these anomalies—including the origin, course, and drainage - is essential for optimal decision making and surgical planning 2,5-8. Several imaging modalities are used to evaluate these anomalies, including echocardiography, multidetector computed tomography (MDCT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and catheter angiography9. Although echocardiography is the initial diagnostic modality in most cases, it is often limited by operator dependency and restricted acoustic window1,3,8,10. In contrast, MDCT offers a comprehensive, non-invasive method for the detailed visualization of anomalous venous connections in patients with CHD3,11.

Systemic and pulmonary venous anomalies are relatively uncommon. Systemic venous anomalies occurr in approximately 0.3–0.4% of the general population, seen in 0.3–0.5% in individuals with normal cardiac anatomy and up to 4.5–10% in those with CHD5,6. Among pulmonary venous anomalies, Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection (TAPVC) is a rare but clinically significant congenital cardiac malformation, accounting for approximately 1-5% of cardiovascular congenital malformations1,4,8,11.

The prevalence of systemic and pulmonary venous anomalies in Southeast Asia remains poorly defined, with most available data derived from global studies. Echocardiography is still widely used in countries like Bhutan and India for the evaluation of these anomalies. However, echocardiography is operator-dependent, has a limited acoustic window, and cannot accurately delineate the drainage pathways of these venous anomalies. This paucity of local data highlights the need for a detailed assessment using MDCT to better understand the burden and variations of venous anomalies in children with CHD in the region. This study aims to review the MDCT findings in various systemic and pulmonary venous anomalies and to highlight the role of MDCT in the comprehensive evaluation of venous anomalies associated with CHD.

METHODS

Study design

A retrospective descriptive study was conducted at the Sir Ganga Ram Hospital.

Study setting

The study was conducted at the (CT) scan Department of Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, a tertiary-care referral centre in New Delhi, India. The hospital has a well-established Radiology Department equipped with X-ray, ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and interventional radiology services. The CT unit is staffed by eight radiologist and serves as a key diagnostic facility within the department. It also functions as an important teaching centre for postgraduate and fellowship trainees. On average, the unit performs about 60 CT examinations per day, reflecting its high service volume.

Study participants

From January 2013 to August 2022, a total of 1,024 patients with an echocardiographic diagnosis of CHD were referred to the CT Department of Sir GangaRam Hospital. Of these, 99 children aged 18 years or younger were identified with systemic or pulmonary venous anomalies and were included in this analysis. Patients with abnormal renal function, a known allergy to contrast media, or those who underwent MDCT for indications other than systemic or pulmonary venous anomalies were excluded. This retrospective descriptive study was granted a waiver of informed consent from parents or guardians.

Sample size

Consecutive sampling was done so all eligible participants meeting the inclusion criteria were included in the study.

MDCT angiography Procedure

All scans were performed using a 128-slice MDCT scanner (Philips Medical System, The Netherlands). Multiphase sequential imaging was obtained at the pulmonary arterial (12-15 seconds) and pulmonary venous (20 seconds) phases, extending from the thoracic inlet to the first lumbar vertebra. A delayed phase scan (60 seconds) was additionally acquired in cases with suspected obstruction to allow collateral vessels to fill the stenotic segments, during post-operative evaluations, and for the evaluation of the Inferior Vena Cava (IVC). The optimized scanning parameters included a gantry rotation time of 0.42 seconds, detector configuration of 64× 0.625, pitch of 1.385, section thickness of 0.67mm, and section increment of 0.67 mm. Contrast media (Omnipaque, 300 mg/mL) was administered intravenously through a 24-gauge cannula at a dose of 2ml/kg body weight, followed by a saline flush using a dual-head Medrad pressure injector. A weight-based low voltage (80-100 kVP) was applied and the automatic tube current modulation was performed using the Care Dose protocol to minimize radiation dose. The contrast injection flow rate was adjusted according to the child’s body weight (2.0-3.0 ml/second). The Computed Tomography Dose Index (CTDI) values ranged between 12.17 to 15.15 mGy.

Statistical analysis

The patient’s findings were collected from CT reports and images archived in the CT unit, coded in a Microsoft Excel sheet, and analyzed. Qualitative data are presented as frequencies and percentages.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was granted by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, as per approval number EC/10/22/2161. As this was a retrospective descriptive study, a waiver of informed consent from parents or guardians was also granted. Data anonymization was done using the hospital registration number as the patient identifier. Personal details of the patients were not shared with any individual or organization, and all data were stored on a password-protected computer of the principal investigator.

RESULTS

A total of 99 patients who underwent MDCT for venous anomalies were included. Males outnumbered females (63.6% versus 36.4%), with ages ranging from birth to 16 years. Of the included participants, 78 had systemic venous anomalies, and 37 had pulmonary venous anomalies. Nine patients had concomitant systemic and pulmonary venous abnormalities.

Systemic venous anomalies

As shown in Table 1, Persistent left superior vena cava (PLSVC) was the most frequently observed systemic venous anomaly, identified in 62 of the 78 patients (79.4%). Among these, 8 had associated pulmonary venous anomalies, 4 had an interrupted IVC, and 1 patient had both an interrupted IVC and a partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection (PAPVC). Interrupted IVC was the second most common anomaly, observed in 6 patients (7.6%), followed by retroaortic left innominate vein in 3 patients (3.8%). Other less frequent anomalies are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Distribution of systemic venous anomalies amongst the participants undergoing MDCT at Sir Ganga Ram CT Department, Jan 2013 – August 2022 (n=78)

|

Systemic venous anomalies |

Frequency (n, %) |

|

Persistent left superior vena cava |

62 (79.4) |

|

Interrupted Inferior vena cava |

6(7.6) |

|

Retroaortic left innominate vein |

3(3.8) |

|

Retroesophageal left innominate vein |

1(1.2) |

|

Double left innominate vein |

3(3.8) |

|

Left innominate vein coursing posterior to the right innominate artery |

2(2.5) |

|

Right-sided superior vena cava draining into the left atrium |

1(1.3) |

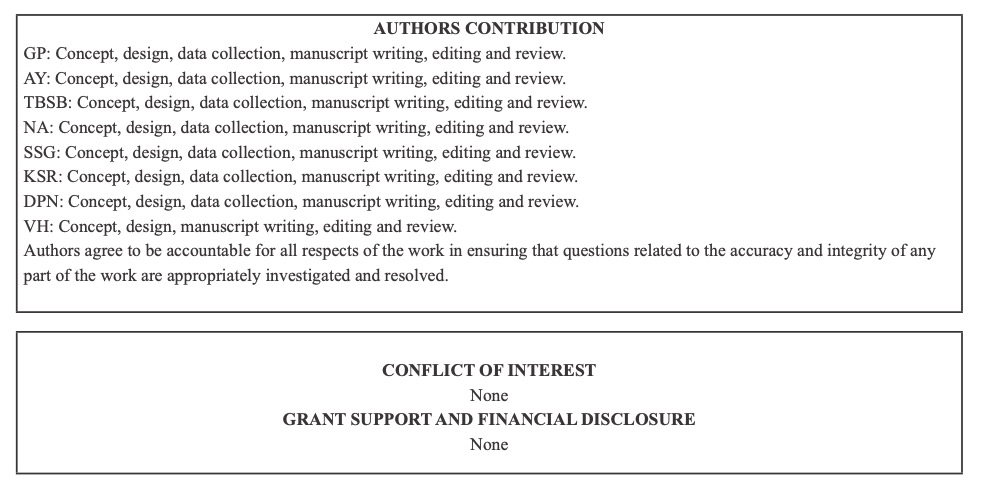

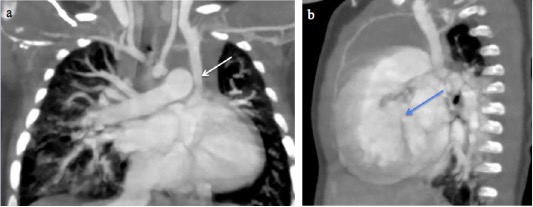

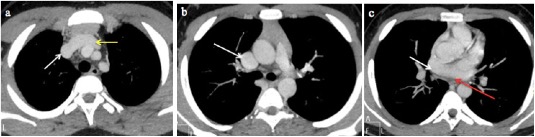

The Figures 1–3 highlight the spectrum of systemic venous anomalies encountered in this study, including a persistent left superior vena cava (PLSVC), a right superior vena cava draining into the left atrium, and a retroaortic left innominate vein, along with their associated cardiac anomalies.

Fig. 1 A 10-month-male infant with Tetralogy of Fallot. a) CT Pulmonary angiography and Coronal Maximum Intensity Projection (MIP) image shows a persistent left superior vena cava (white arrow). b) Coronal MIP image shows a ventricular septal defect (blue arrow).

Fig. 2 A 14-year-old boy with a right superior vena cava draining into the left atrium. (a-c) Sequential axial MIP images from cranial to caudal levels show the right SVC (white arrow) draining into the left atrium (red arrow). Left brachiocephalic vein is also seen (yellow arrow).

Fig. 3 A 2-month-old male infant with tetralogy of Fallot and a retroaortic left innominate vein. (a, b) CTPA axial MIP images show the retroaortic left innominate vein (white arrow). c) Axial MIP image shows a ventricular septal defect (yellow arrow). d) Sagittal MIP image shows overriding of the aorta (red arrow). e) Axial MIP image shows a right-sided aortic arch (white arrow). f) Axial MIP image shows narrowing of the main pulmonary artery (green arrow), and its right and left branches.

AA: Ascending aorta, RA: Right atrium, LA: Left atrium, RV: Right ventricle, LV: Left ventricle

Pulmonary venous anomalies

As shown in Table 2, Partial Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection (PAPVC) was the most common pulmonary venous anomaly, detected in 18 of the 37 patients (48.6%) with pulmonary venous anomalies. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC) was the next most common anomaly, present in 11 patients (29.7%).

The most common drainage site of PAPVC on the right side was the SVC (n=4), while on the left side, it was the left innominate vein (n=6). Other less frequent drainage sites included the right atrium (n=3), IVC (n=3), coronary sinus (n=2), and azygos vein (n=1). Among patients with TAPVC, the supracardiac type was the most common, with drainage into the SVC (n=6) and left innominate vein (n=1). In the cardiac type (n=2), the anomalous veins drained into the common atrium and right atrium. One patient had the infracardiac type, where drainage occurred into the splenic vein, while another had a mixed type, with connections to both the SVC and right atrium.

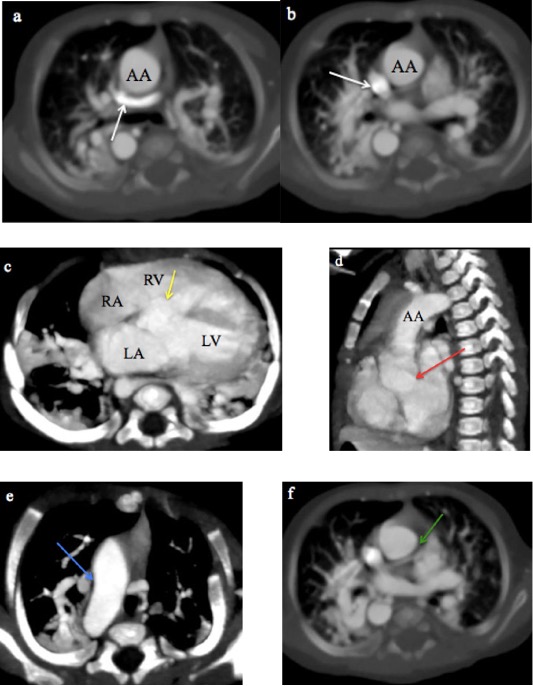

MDCT images of TAPVC are shown in Figures 4 and 5, demonstrating the characteristic drainage patterns of the supracardiac and infracardiac types, respectively.

Table 2: Distribution of pulmonary venous anomalies amongst the participants undergoing MDCT at Sir GangaRam CT Department, Jan 2013 – August 2022 (n=37)

|

Pulmonary venous anomalies |

Frequency (n, %) |

|

Partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection |

18 (48.6) |

|

Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection |

11 (29.7) |

|

Pulmonary vein stenosis |

8(21.6) |

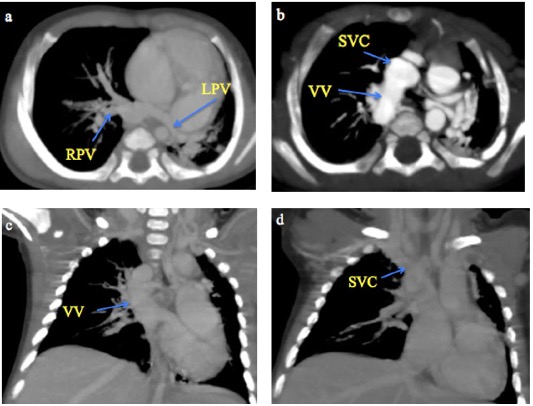

Fig. 4 A 2-month male infant with supracardiac total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. (a-b) CT Pulmonary angiography axial MIP sequential images from caudal to cranial levels showing the left pulmonary veins (LPV) and right pulmonary veins (RPV) converging to form a vertical vein (VV) that drains into the superior vena cava (SVC). (c-d) Coronal MIP images demonstrating the VV draining into the SVC.

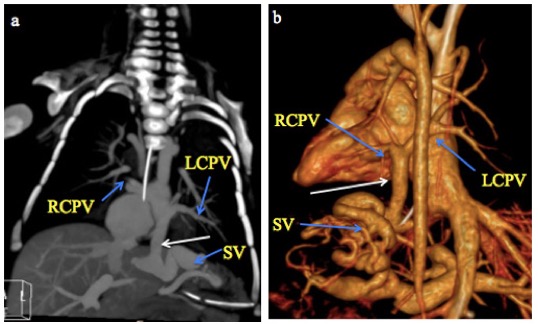

Fig. 5 A month old male infant with infracardiac total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. a) CT Pulmonary angiography coronal MIP and b) 3-D volume-rendered CT images show the right and left superior and inferior pulmonary veins (RCPV and LCPV) joining to form a vertical vein (white arrow) that descends through the diaphragm and drains into a dilated and tortuous splenic vein (SV).

DISCUSSION

MDCT has emerged as a highly accurate and noninvasive modality for delineating systemic and pulmonary venous anomalies in patients with complex CHD3. Its multiplanar reconstruction capabilities enable precise visualization of anatomy, which is often challenging to assess through echocardiography alone. This is particularly valuable in the pre-operative setting where accurate anatomical mapping can guide surgical planning and prevent intraoperative complications.

Persistent left superior vena cava is the most common systemic venous anomaly5. PLSVC most commonly drains into the right atrium9. Abnormal drainage of PLSVC into the left atrium is very rare6. In cases of situs ambiguous, the drainage site can vary and may include the left atrium, right atrium, common atrium, or azygos vein4,5. In this study, of 62 cases of PLSVC, four patients with associated situs ambiguous had drainage into the common atrium and azygos vein5. Consistent with previous literature, PLSVC was often found alongside septal defects, supporting the embryological connection between venous and atrial development pathways1.

A right-sided SVC draining into the left atrium is an extremely rare anomaly, representing less than 0.5% of all CHD cases 8,9. In our study, we identified one such case (Figure 2), comparable to a case reported by Usalp S et al18. This highlights the importance of carefully tracing the entire course of the SVC during imaging to avoid missed diagnosis. Reported cardiac anomalies commonly associated with this condition include single atrium or uni-ventricular heart, tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), and transposition of great arteries (TGA) 9.

Interrupted IVC is frequently associated with complex congenital anomalies such as heterotaxy syndrome with left isomerism, situs inversus, situs ambiguous, ASD, VSD, double outlet right ventricle (DORV), TAPVC, and PLSVC 19-21. In this study, all six patients with interrupted IVC had situs ambiguous and left isomerism, accompanied by additional cardiac malformations such as TOF, ASD, double aortic arch, DORV, TGA, univentricular heart, and PAPVC. MDCT effectively delineated the anomalous venous pathways, revealing that in five of six patients, the left-sided interrupted IVC drained into the PLSVC via the hemi-azygos vein before reaching the right atrium. Notably, an interrupted IVC is the most common cause of enlarged azygous vein, which on thoracic CT may mimic right paratracheal mass or retro crural lymphadenopathy20,22. Therefore, MDCT angiography of the thorax and abdomen is essential for accurate classification of the venous drainage pathways and identification of associated cardiac malformations.

Various innominate vein anomalies were identified in this study, including retroaortic left innominate vein (Figure 3), retroesophageal left innominate vein, double left innominate vein and left innominate vein coursing behind the right innominate artery. These aberrant courses are commonly associated with CHD involving right outflow obstruction, such as TOF4,16-17. Other cardiac malformations linked to these anomalies include pulmonary atresia, VSD with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), VSD with TAPVC, right aortic arch, and PDA4,16,17,23. In this study, similar associations were noted such as pulmonary atresia, TOF, right-sided aortic arch, septal defects and one case of truncus arteriosus. While echocardiography and catheter angiography can identify these left innominate vein anomalies, MDCT offers superior cross-sectional visualization, allowing for comprehensive anatomical delineation5-17.

MDCT is invaluable in detecting PAPVC, a condition in which one or more pulmonary veins drain into the right atrium instead of the left atrium. PAPVC is more frequent on the right side4,8,10. In our study, right-sided PAPVC was more common and the typical drainage sites mirrored those reported in literature – the SVC and the right atrium on the right and into the left innominate vein on the left8,10. Our study identified a rare case of left hemi-PAPVC, similar to a case reported by Murali VP et al24. The most common type of PAPVC was drainage of the right superior pulmonary vein, followed by drainage of all right pulmonary veins, left superior pulmonary vein, total left pulmonary veins and the right inferior pulmonary vein. The PAPVC involving both sides constitutes between 0.9-1.6% of all reported cases24. PAPVC often coexisted with ASD and VSD, PDA and PLSVC, findings consistent with earlier studies8,10,25.

TAPVC, in which all four pulmonary veins drain into the systemic veins rather than the left atrium, is usually diagnosed on echocardiography4. However, MDCT angiography is indispensable when echocardiographic visualization is limited or complex CHD is suspected. The supracardiac type of TAPVC was the most common in this study (45.5%), consistent with previous reports (45%-55%)8,10. In our study, MDCT angiography effectively characterised various drainage patterns, including a supracardiac TAPVC draining into the SVC and a rare infracardiac type of TAPVC draining into the splenic vein, also reported by AI Mutari et al26. MDCT’s 3D reconstructions provided crucial details for accurate delineation of venous stenosis.

Congenital pulmonary vein stenosis is a rare anomaly, occurring in 0.03 – 0.4% of CHD cases often associated with TAPVC, septal defects and TGA27,28. In our study, most cases occurred in conjunction with septal defects or post-operative TAPVC.

A complete description of the anomalous vein’s course, drainage site, and associated congenital cardiac defects is essential for accurate diagnosis, surgical planning and optimal management. As is the dictum in the evaluation of patients with CHD, one must never assume normal anatomical positioning. MDCT remains a cornerstone modality for comprehensive, noninvasive evaluation of both systemic and pulmonary venous anomalies.

Limitations

This single-center retrospective review has certain limitations. The sample size was small, and only patients with suspected preoperative extracardiac anomalies were included. As a tertiary referral center study, referral bias may have led to over-representation of complex or atypical cases. The retrospective design also carries potential data and interpretation bias. Additionally, the absence of surgical or long-term follow-up correlation limits validation of the imaging findings. A comprehensive multimodality analysis was beyond the scope of this study.

CONCLUSION

MDCT is a non-invasive imaging modality that enables a comprehensive evaluation of pulmonary, systemic, and associated cardiac anomalies. Its high-resolution and multiplanar reformation (MPR) capability enables precise identification of venous abnormalities often missed by other modalities, providing radiologists with essential details for accurate diagnosis.

REFERENCES

1. Dillman JR, Yarram SG, Hernandez RJ. Imaging of pulmonary venous developmental anomalies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(5):1272–85. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

2. Marini TJ, He K, Hobbs SK, KaprothJoslin K. Pictorial review of the pulmonary vasculature: from arteries to veins. Insights Imaging. 2018;9(6):971–87. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

3. Elbeih DF, ElGohary MM, Shebrya NH, Saleh MA. Value of multidetector Computed Tomography in Evaluation of Thoracic Venous Abnormalities among Pediatrics with Congenital Heart Disease. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2013;51:376–84. [Full Text] [DOI]

4. Lyen S, Wijesuriya S, NganSoo E, Mathias H, Yeong M, Hamilton M, et al. Anomalous pulmonary venous drainage: a pictorial essay with a CT focus. J Congenit Cardiol. 2017;1:1–3.[Full Text] [DOI]

5. Arslan D, Cimen D, Guvenc O, Bulent OR. The anomalies of systemic venous connections in children with congenital heart disease. Eur J Gen Med. 2014;11:33–7.[Full Text] [DOI]

6. Corno AF, Alahdal SA, Das KM. Systemic venous anomalies in the Middle East. Front Pediatr. 2013;1:1.[PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

7. Shehata S, Abdulmonaem G, Gamal A, Assy M. Spectrum of thoracic systemic venous abnormalities using multidetector computed tomography. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2022;53:1–7.[Full Text] [DOI]

8. Pandey NN, Sharma A, Jagia P. Imaging of anomalous pulmonary venous connections by multidetector CT angiography using thirdgeneration dualsource CT scanner. Br J Radiol. 2018;91(1092):20180298. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

9. Azizova A, Onder O, Arslan S, Ardali S, Hazirolan T. Persistent left superior vena cava: clinical importance and differential diagnoses. Insights Imaging. 2020;11(1):110. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

10.Gözgeç E, Kantarci M, Guven F, Ogul H, Ceviz N, Eren S. Determination of anomalous pulmonary venous return with highpitch lowdose computed tomography in pediatric patients. Folia Morphol. 2021;80(2):336–43.[PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

11.Turkvatan A, Tola HT, Ayyildiz P, Ozturk E, Ergul Y, Guzeltas A. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection in children: preoperative evaluation with lowdose multidetector computed tomographic angiography. Tex Heart Inst J. 2017;44(2):120–26. [Pub Med] [Full Text] [DOI]

12.Batouty NM, Sobh DM, Gadelhak B, Sobh HM, Mahmoud W, Tawfik AM. Left superior vena cava: crosssectional imaging overview. Radiol Med. 2020;125(3):237–46.[PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

13.Baggett C, Skeen SJ, Gantt DS, Trotter BR, Birkemeier KL. Isolated right superior vena cava drainage into the left atrium was diagnosed noninvasively in the peripartum period. Tex Heart Inst J. 2009;36(6):611-14. [PubMed] [Full Text]

14.Li SJ, Lee J, Hall J, et al. The inferior vena cava: anatomical variants and acquired pathologies. Insights Imaging. 2021;12(1):123. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

15.Kobayashi K, Uchida T, Kuroda Y, Yamashita A, Ohba E, Nakai S, Ochiai T, Sadahiro M. Double left brachiocephalic vein in an adult patient who underwent cardiac surgery: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;16(1):245. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

16.Goel AN, Reyes C, McLaughlin S, Wittry M, Fiore AC. Retroesophageal left brachiocephalic vein in an infant without cardiac anomalies. Prenatal Cardiol. 2016;6:87–9. [Full Text] [DOI]

17.Kulkarni S, Jain S, Kasar P, Garekar S, Joshi S. Retroaortic left innominate vein – incidence, association with congenital heart defects, embryology, and clinical significance. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;1(2):139–41.[PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

18.Usalp S, Karaci AR, Balcı KG, Yazicioglu V, Baskurt M, et al. Right superior vena cava draining into the left atrium. Clin Med Rev Case Rep. 2016;3(10):320–2. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

19.Liu Y, Guo D, Li J, et al. Radiological features of azygos and hemiazygos continuation of inferior vena cava: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(17):e0546. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

20.Chen SJ, Wu MH, Wang JK. Clinical implications of congenital interruption of inferior vena cava. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022;121(10):1938–44.[PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

21.Zafar SI, Halim A, Khalid W, Shafique M, Nasir H. Two Cases of Interrupted Inferior Vena Cava with Azygos/Hemiazygos Continuation. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2023;32(8):S101–3.[PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

22.Verma M, Khurana R, Malhi AS, Kumar S, Kothari SS. Retroesophageal left brachiocephalic vein in tetralogy of Fallot: an anomalous course depicted on computed tomography angiography. Acta Cardiol. 2022;77(6):562–3.[PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

23.Murali VP, Bahuleyan CG, Jayakumar K, Ramanarayan PV, Nair GR. Hemianomalous pulmonary venous connection of the left lung surgically corrected. Chest. 1992;101(6):1718–19.[PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

24.Lewis RA, Billings CG, Bolger A, Bowater S, Charalampopoulos A, et al. Partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage in patients presenting with suspected pulmonary hypertension: a series of 90 patients from the ASPIRE registry. Respirology. 2020;25(10):1066–72.[PubMed][Full Text] [DOI]

25.AlMutairi M, Aselan A, AlMuhaya M, AboHaded H. Obstructed infracardiac total anomalous pulmonary venous connection: the challenge of palliative stenting for the stenotic vertical vein. Pediatr Investig. 2020;4(2):141–4. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

26.PazosLópez P, GarcíaRodríguez C, GuitiánGonzález A, et al. Pulmonary vein stenosis: Etiology, diagnosis and management. World J Cardiol. 2016;8(1):81-8. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

27.Fujii T, Tomita H, Kise H, Fujimoto K, Kobayashi K, et al. An infant with primary pulmonary vein stenosis, associated with fatal occlusion of intraparenchymal small pulmonary veins. J Cardiol Cases. 2013;9(1):3-7. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]