INTRODUCTION

Bhutan’s Constitution mandates free basic public health services in both modern medicine and traditional medicine (Gso-ba Rigpa), ensuring accessible healthcare to its citizens1. Developmental activities and health policies are guided by the philosophy of Gross National Happiness, which emphasizes holistic well-being alongside economic progress2.

Bhutan’s modern healthcare system was launched with the first Five-Year Plan in 19613. While it initially focused on strengthening primary health care, it gradually expanded to include specialized services, including anesthesia and surgery. Bhutanese traditional medicine, dating back to the seventh century, includes gso-ba rigpa (formal practice) and local healers3. The National Institute of Traditional Medicine trains Drungtshos (traditional physicians) and Menpas (physician assistants) while local healers acquire their knowledge and skills through family lineage, mentorship or self-learning, often without formal training 4.

Although its beginnings date back to the 1960s, there is limited documentation regarding anesthesia practices in both traditional and modern medicine in Bhutan. This perspective explores the historical evolution of anesthesia services in the country, while also highlighting the challenges faced and future prospects in this field.

The early days of anesthesia in Bhutan

Bhutanese traditional medicine does not document the use of anesthesia for surgical procedures. However, local healers performed spiritual rituals, and utilized herbal remedies along with the ingestion of alcohol to manage pain. In gso-ba rigpa, common pain management therapies include gold needle (serkhap), silver needle, heated oil cauterization, steam bathing, and bloodletting.

In modern medicine, the earliest recorded use of anesthesia in Bhutan dates back to 1864, when Dr. Benjamin Simpson, a British doctor accompanying a political mission, used chloroform to operate on a man with a facial tumor in Samtse4. In 1966, Dr. Gottfried Riedel, a German volunteer, administered Bhutan’s first regional anesthesia (lumbar anesthesia) to perform a cesarean section. Despite lacking formal training in anesthesia or surgery, he successfully performed the procedure by following instructions from a medical textbook4.

When anesthesia services first began in Bhutan, open-drop ether was used, administered via a Schimmelbusch mask, an ether bottle, and a Goldman vaporizer. By the late 1990s, BOC Boyle’s machines (Apparatus Mark II) with vaporizers (Boyle's bottle) were introduced, enabling the administration of inhalational agents such as ether, halothane and trilene. Reusable rubber endotracheal tubes were used for airway management, while autoclaved stainless-steel spinal needles in sizes 18G, 20G, and 22G were used for spinal anesthesia. Peripheral intravenous (IV) access involved hypodermic needles sized 18G and 20G. IV fluids were supplied in glass bottles and delivered via reusable rubber tubing.

Available anesthetic drugs included thiopentone, ketamine, succinylcholine, gallamine, pancuronium, tubocurarine, neostigmine, and atropine. Hyperbaric lidocaine was the only spinal anesthesia agent. Hospitals frequently faced shortages of anesthetic drugs and oxygen supplies.

The development of anesthesia services and training in Bhutan

In the 1970s and 1980s, only three hospitals in Bhutan – Thimphu, Gelephu, and Trashigang - provided basic anesthesia and surgical services. These services were provided by anesthesiologists and surgeons from India and Myanmar. Among them, Dr. G.C. Sharma, an anesthesiologist from Assam, India, served at Thimphu General Hospital in the 1970s, possibly as Bhutan’s first physician anesthesiologist, staying until the 1980s. After his departure, Dr. Sarkar and Dr. Yanki Shipmo from India joined in 1983, followed by UN volunteer Dr. Phone Gyaw in 19845.

In 1998, Dr. Jampel Tshering completed his training in Myanmar, becoming Bhutan’s first physician anesthesiologist. He briefly worked at the Thimphu General Hospital before being transferred to Dewathang Hospital due to militancy issues along the Indian border5. In 1999, Dr. Singye Dorji, a Sri Lankan graduate, became the first Bhutanese physician anesthesiologist to lead the department at Thimphu General Hospital. He introduced standardized surgical protocols, modernized anesthesia equipment, established the hospital’s intensive care unit (ICU), and trained ICU staff 4,5.

Anesthesia training in Bhutan began informally in 1988, when Dr. Shipmo trained two Bhutanese nurses, Mr. Singye and Mr. Lungten Jamtsho, at the Thimphu General Hospital. The six-month intensive training focused on providing general and spinal anesthesia, producing Bhutan’s first anesthesia practitioners. However, the initiative lacked a formal curriculum and teaching faculty, relying solely on the trainer’s expertise.

Formal anesthesia training was established in 2014, when Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan (KGUMSB) launched a postgraduate training program in anesthesia with one resident. Despite limited faculty and infrastructure, the program has produced nine physician anesthesiologists as of June 2025, with four currently in training. However, the number of candidates enrolling in the program remains inconsistent, with some years seeing no intake.

To address the persistent shortage of anesthetists, the Ministry of Health (MoH), in collaboration with the Royal Civil Service Commission (RCSC), introduced a two-year Bachelor of Science in Nurse Anesthesia program at the Faculty of Nursing and Public Health (FNPH) in 2014. Unfortunately, only one cohort of five nurses graduated, and no subsequent batches were enrolled. To bridge this gap, the MoH initiated international training by sending nurses to Thailand, where approximately 30 nurses have successfully completed anesthesia training to date.

Anesthesia technicians, often referred to in Bhutan as operation theater (OT) technicians, assist anesthetists in delivering safe anesthesia care. Initially, Bhutan lacked dedicated anesthesia /OT technicians and relied on ward assistants and scrub nurses. As the need for OT technicians grew, FNPH introduced OT technician training in 1998. The program was briefly halted when the perceived workforce need was met but was reinstated in 2019 to meet the growing demands from expanding surgical centers and the introduction of new surgical subspecialties.

Current anesthesia and surgical services

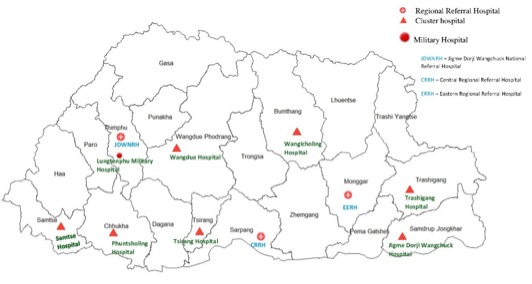

Bhutan currently has 11 hospitals providing anesthesia and surgical services, strategically positioned based on accessibility, population and disease burden (Figure 1). Regional hospitals offer comprehensive anesthesia and surgical services, while cluster hospitals primarily provide essential services such as obstetric and general surgery. Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital (JDWNRH) functions as the apex referral center for specialized anesthesia and surgical services (Table 1). All centers are equipped with modern anesthesia machines and standard monitoring systems.

However, subspecialty services like cardiothoracic, vascular, and transplant surgeries remain unavailable, as do many onco-surgeries, with the exception of those for head and neck, gastrointestinal, and gynecological cancers. Although pediatric and neurosurgeries are performed by trained physician anesthesiologists, the absence of dedicated surgical ICUs limits their full potential. Similarly, pain management and palliative care services remain underdeveloped.

Figure 1. Hospital in Bhutan with anesthesia and surgical services, 2025

Table 1. Current anesthesia and surgical services in Bhutan

|

Hospital category |

Hospitals |

Services |

|

Regional Referral Hospitals |

JDWNRH (Thimphu) CRRH (Gelephu) ERRH (Mongar)

|

CRRH and ERRH provides obstetrics and gynecological, orthopedics, ENT, ophthalmology, general surgery, sedation for CT scan/endoscopies JDWNRH: In addition to the above services, sedation for ECT, pediatric surgery, neurosurgery, urological surgeries, oncosurgeries for Head and Neck, Gastrointestinal (GI), and Gynecology.

|

|

District / Cluster hospitals |

Bumthang (Wangdicholing) Jigme Dorji Wangchuck (Dewathang) Phuntsholing Samtse Trashigang Tsirang(Damphu) Wangdue

|

All hospitals provide general surgery and obstetrics and gynecological surgical and anesthesia service Samtse and Wangdue hospitals provide additional ophthalmology surgical and anesthesia services Phuntsholing hospital provides additional ENT, orthopedics and ophthalmology surgical and anesthesia services

|

|

Military Hospital |

Lungtenphu Military Hospital |

Provides general surgery, obstetrics and gynecological, and ophthalmology surgical and anesthesia services |

JDWNRH: Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital; CRRH: Central Regional Referral Hospital; ERRH: Eastern Regional Referral Hospital; ENT: Ear Nose Throat; CT: Computed Tomography; ECT: Electro Convulsive Therapy

Current anesthesia workforce

As of January 2025, Bhutan’s anesthesia workforce includes 12 regular physician anesthesiologists, one on contract, and five expatriate physician anesthesiologists from Myanmar. They are supported by 23 nurse anesthetists and 56 OT technicians across the country. Among the Bhutanese physician anesthesiologists, two have specialized training in pediatric anesthesia, and one each in acute pain and regional anesthesia, neuro-anesthesia, and critical care. Due to the limited number of physician anesthesiologists, anesthesia services in most district hospitals are managed by nurse anesthetists.

Challenges and Way Forward

With the expansion of surgical services, Bhutan faces a shortage of anesthetists. The World Federation of Societies of Anesthesiologists (WFSA) recommends a minimum of five physician anesthesiologists per 100,000 population6. However, with only 173 general doctors nationwide, achieving this target remains impossible7. Only a few MBBS doctors pursue anesthesiology, often perceiving it as a “stressful” and “behind-the-scene” profession that lacks the recognition accorded to surgeons and physicians.

As a practical short-term solution, the MoH and RCSC should continue investing in the training of nurse anesthetists. Nurse anesthesia programs require only 12 months of training compared to 3-5 years for physician anesthetists. However, this pathway is often undermined by a lack of professional recognition, incentives, and career advancement opportunities, which discourage candidates from pursuing the program. Furthermore, after graduation, both nurse anesthetists and OT technicians receive limited opportunities for Continuing Medical Education (CME), restricting their professional growth and skill development.

Bhutan’s uniform pay structure, in which all professionals are paid equally based on the RCSC’s position classification system regardless of their specialty, is another deterrent. This system does not account the healthcare sector’s complexity, diverse responsibilities, and workload. Therefore, agencies such as the MoH, National Medical Services (NMS), Bhutan Qualification and Professionals Certification Authority (BQPCA), and RCSC must address these challenges. Introducing specialty-based incentives, risk allowances, and clear career development pathways are some of the measures to improve enrollment, ensure retention and maintain a sustainable anesthetist workforce.

Additionally, the RCSC, in collaboration with the NMS and BQPCA, should consider renaming OT technicians as anesthesia technicians. While OT technicians primarily focus on surgical equipment and assisting surgeons, anesthesia technicians assist anesthetists in setting up and administering anesthesia procedures. Their job descriptions differ significantly, making renaming necessary for clarity and recognition.

Bhutanese anesthetists have yet to establish a national anesthesia association, leaving them underrepresented on the international stage. Forming such an association would create opportunities for collaboration with regional and global organizations such as the WFSA. Such a network would enable Bhutanese anesthetists to participate in international workshops, training programs, webinars, and seminars, thereby enhancing their professional development. Ultimately, this would strengthen the quality of anesthesia services in the country.

CONCLUSION

Since the inception of the first Five-Year Plan, Bhutan has made significant progress in health care. Nonetheless, the country continues to face a shortage of physician anesthesiologists. To further advance the field of anesthesia, continuous effort is required from relevant stakeholders to reassess the current system. Additionally, professional recognition and the provision of incentives are essential for maintaining and expanding anesthesia services in Bhutan.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author is deeply indebted to Mr. Singye, one of the first Bhutanese nurse anesthetists, for providing his insightful narrative on the evolution of anesthesia in Bhutan.

REFERENCES

1. The Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan. 2008; 64p. [Full Text]

2. Sithey G, Thow AM, Li M. Gross national happiness and health: lessons from Bhutan. Bull World Health Organ. 2015; 93(8): 514. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

3. Royal Government of Bhutan. Ministry of Health. The advent of Modern Health services in Bhutan. [Full Text]

4. Dorji T, Melgaard B. Medical History of Bhutan: Chronicle of Health and Disease from Bon Times to Today. 2nd ed. Bhutan: Centre for Research Initiatives; 2018. 174p.

5. Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital. Annual Report 2017. Thimphu, Bhutan. Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital; 2018.

6. Kempthorne P, Morriss WW, Mellin-Oslen J, Gore-Booth J. The WFSA Global Anesthesia Workforce Survey. Anesth Analg. 2017; 125(3):981-990. [PubMed] [Full Text] [DOI]

7. Ministry of Health: Annual Health Bulletin 2025. Thimphu: Health Management Information System and Research Section, Policy and Planning Division, Ministry of Health, Royal Government of Bhutan. [Full Text]